Around the world Posted on 2021-12-20 15:20:38

Success stories

Putting OIE international standards into practice, to support countries’ claims of freedom from disease and to facilitate safe international trade

Lessons learnt from practices of OIE Members for the implementation of OIE standards

Keywords

Authors

Members of the Reference Group for the OIE Observatory.

The designations and denominations employed and the presentation of the material in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the OIE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries.

The views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s). The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the OIE in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

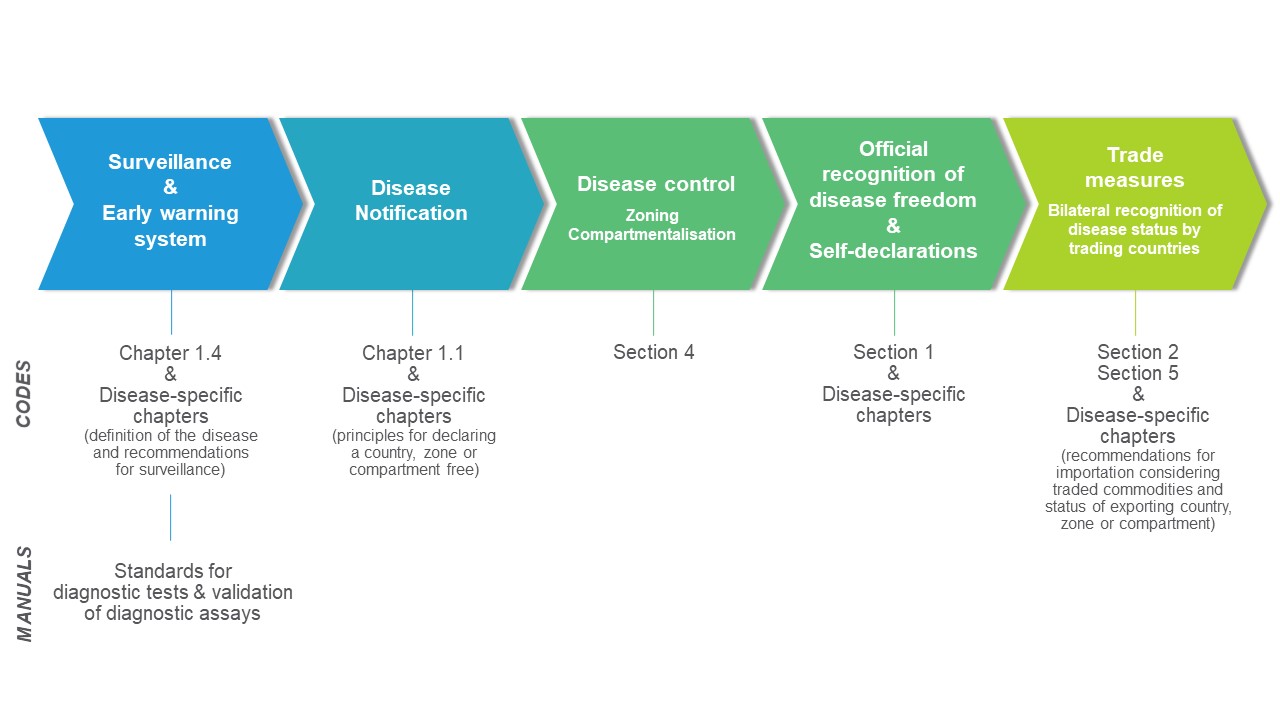

The process of putting OIE standards into practice involves a continuum of measures from surveillance, through to the notification and control of diseases, to trade measures (see diagram).

This continuum consists of a series of processes, illustrated by the following examples.

Implementation of OIE standards by laboratories to carry out veterinary diagnostic tests and surveillance

The Veterinary Research Institute of Tunisia is the national Reference Laboratory for the diagnosis of major animal diseases. The laboratory draws on its full range of expertise to assist health authorities in decision-making. In order to harmonise and improve the quality of diagnostic testing in the virology laboratory, two OIE twinning projects were carried out, with the aim of developing a reliable and sensitive diagnostic in accordance with OIE standards [5, 6]. The risk of expansion of emerging diseases, including Rift Valley fever (RVF), in previously disease-free regions requires the implementation of effective surveillance programmes for animal populations. To achieve this, it is pivotal to regularly assess the performance of existing diagnostic tests, and to evaluate the capacity of veterinary laboratories to detect RVF infection in an accurate and timely manner. In this context, several external quality assessments were organised to examine the diagnostic capacities of veterinary laboratories [7, 8].

Implementation of OIE standards to support disease freedom claims

National animal disease surveillance programmes may differ from one country to another, according to their specific production systems and epidemiological situation. Therefore, OIE standards are result-oriented and do not prescribe specific models. This creates a variable array of implementation patterns across the world. Nevertheless, the need to comply with the notification obligations laid down in Chapter 1.1. of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Animal Health Codes [1, 2] through the OIE-WAHIS reporting system, and the provision of structured frameworks for official recognition of free status and for self-declaration of disease-free status, allows for some harmonised implementation.

Implementation of OIE standards to control animal diseases and ensure the safety of international trade

In the Terrestrial and Aquatic Animal Health Codes, Sections 2 and 5, alongside various disease-specific chapters [1, 2], address aspects of trade associated with the principles of the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement), particularly regionalisation. Concepts such as zoning and compartmentalisation have been developed to enable countries to continue to trade safely, even in the event of animal disease outbreaks.

Technical specifications of the People’s Republic of China for the management of specific animal-disease-free zones and for the management of disease-free compartments [9, 10]

In regard to the OIE standards for disease-free zones, free zones have been established in China for foot and mouth disease, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) and specific equine diseases.

In accordance with the OIE principles for disease-free compartments, 6 compartments free from HPAI have been established so far in 4 provinces, and 62 compartments free from African swine fever (ASF) have been established in 25 provinces.

The European Union (EU) policy on prevention, control and eradication of ASF [11]

Regionalisation (or zoning) is at the centre of EU policy on ASF. With legislation and guidelines based on the principles laid down in the relevant OIE standards, the EU aims to prevent the introduction and spread of ASF on its territory by ensuring safe trade of pigs and pig commodities through a comprehensive system of regionalisation. African swine fever remains contained in limited areas of the EU and has already been eradicated in two of its Member States (the Czech Republic and Belgium).

https://doi.org/10.20506/bull.2021.2.3294

References

- World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) (2021). – Terrestrial Animal Health Code.

- World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) (2021). – Aquatic Animal Health Code.

- World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) (2021). – Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals.

- World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) (2021). – Manual of Diagnostic Tests for Aquatic Animals.

- Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Venezie (IZSVe) (2018). – OIE twinning project between the IZSVe and the Tunisian Veterinary Research Institute (IRVT) on the diagnosis of viral encephalopathy and retinopathy.

- Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e del Molise “Giuseppe Caporale” (2016). – Bluetongue diagnosis twinning and cooperation project.

- Monaco F., Cosseddu G.M., Doumbia B., Madani H., El Mellouli F., Jiménez-Clavero M.Á., Sghaier S., Marianneau P., Cetre-Sossah C., Polci A., Lacote S., Lakhdar M., Fernández-Pinero J., Sari Nassim C., Pinoni C., Capobianco Dondona A., Gallardo C., Bouzid T., Conte A., Bortone G., Savini G., Petrini A. & Puech L. (2015). – First external quality assessment of molecular and serological detection of Rift Valley fever in the western Mediterranean region. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142129.

- Pérez-Ramírez E., Cano-Gómez C., Llorente F., Adzic B., Al Ameer M., Djadjovski I., El Hage J., El Mellouli F., Goletic T., Hovsepyan H., Karayel-Hacioglu I., Maksimovic Zoric J., Mejri S., Sadaoui H., Hassan Salem S., Sherifi K., Toklikishvili N., Vodica A., Monaco F., Brun A., Jiménez-Clavero M.Á. & Fernández-Pinero J. (2020). – External quality assessment of Rift Valley fever diagnosis in 17 veterinary laboratories of the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239478.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2016).– Notice of the Ministry of Agriculture on issuing the ‘Technical regulations for the management of animal disease free zones’ [in Chinese].

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2020). – Notice of the General Office of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs on the issuance of the ‘African swine fever free zone standard’ and the ‘Technical specifications for the management of animal disease free zones’ [in Chinese].

- European Commission (2021). – African swine fever.