INFORMATION EN CONTINU Posté sur 2021-01-26 09:24:13

Veterinary workforce development: the relevance of skill qualification, education and occupational frameworks

Mots-clés

Authors

Miftahul I. Barbaruah (1)* & Sonia Fèvre (2)

(1) Vet Helpline India Pvt Ltd., Assam, India.

(2) Capacity Building Department, World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE).

* Corresponding author: drbarbaruah@gmail.com

The designations and denominations employed and the presentation of the material in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the OIE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries.

The views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s). The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the OIE in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

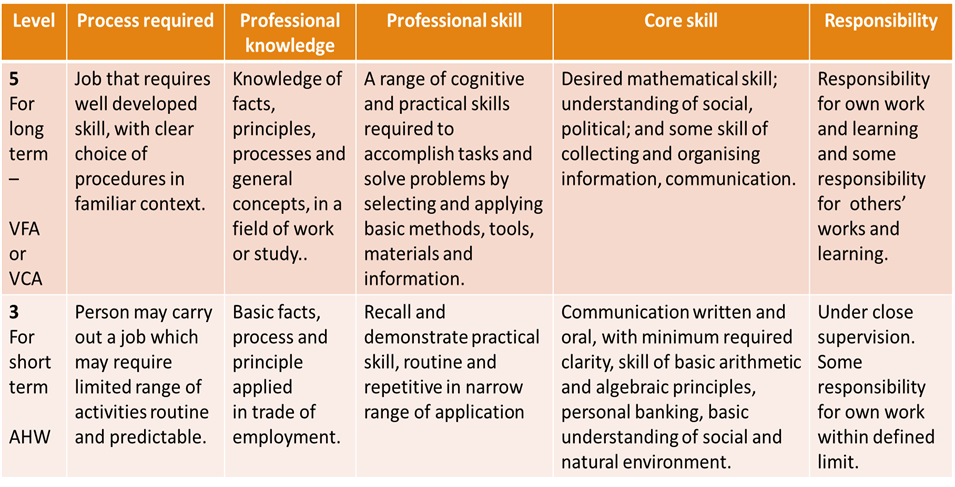

Skill qualification frameworks

A growing trend in workforce planning is to ensure that job descriptions are based on skills and competencies, and that educational programmes ensure that their learning outcomes correspond to relevant job requirements. The alignment of educational qualifications to an internationally comparable framework can help lead to equitable recognition across a country, the harmonisation of certification schemes, and can facilitate lifelong learning and the mobility of those with such qualifications. More than 100 countries have or are in the process of developing national qualification frameworks, and numerous regional frameworks already exist, such as the European Qualifications Framework [1], ASEAN Qualification Reference Framework [2], and the Southern African Development Community Qualifications Framework [3]. National Occupational Standards (NOS), which describe the knowledge, skills and understanding an individual needs to be competent at a job, are already guiding training aimed at industry professionals in various countries. Industry-led certifying bodies that use skill qualification frameworks in the veterinary domain include LANTRA, an awarding body for land-based industries in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland [4]; Rural Skills Australia [5]; and the Agriculture Skill Council of India [6]. Skill qualification frameworks (SQFs) organise qualifications according to levels of knowledge, skills and aptitudes [7, 8], which the learner must possess regardless of whether they were acquired through formal, non-formal or informal learning (Table I).

VFA: Veterinary Field Assistant, VCA: Veterinary Clinical Assistant, AHW: Animal Health Worker.

Source: www.nsda.gov.in/assets/documents/nsqf/NSQF%20LEVEL%20DESCRIPTORS.pdf

International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED)

The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED 2011) [9] is a comprehensive framework for comparing education systems across countries. Veterinary education comes under ISCED Level 7 (Master’s or equivalent, see Section 9B.247 of the ISCED 2011 document published by UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics). The level accorded to education related to veterinary paraprofessionals (VPPs) is not currently specified. However, a review of the ISCED classification of Fields of Education is leading to a more expanded classification of Fields of Education and Training [10] to ensure that vocational training is appropriately represented. Within the ‘Fields of Education’ classification, Veterinary Medicine and Veterinary Assisting fall under Group 6 (Code 64, see annex IV to the abovementioned document).

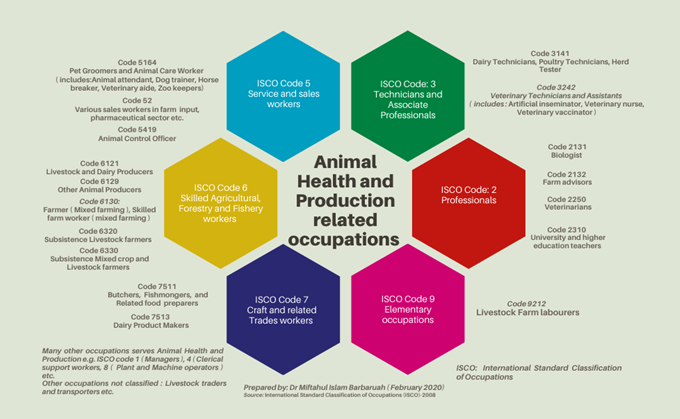

Occupations

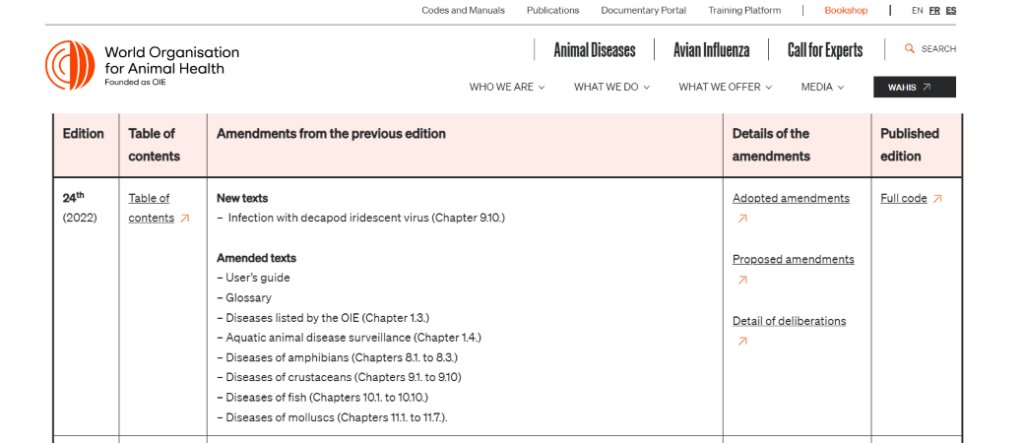

The International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO), developed by the International Labour Organization (ILO) of the United Nations, is a tool for organising jobs into clearly defined groups according to the tasks and duties undertaken. Countries use the ISCO system for classifying and aggregating occupational data. Various statistical applications use ISCO codes for matching jobseekers with job vacancies, the management of short- or long-term migration of workers between countries, and the development of vocational training programmes and guidance. The occupational categories within the veterinary domain vary widely from country to country and standardising these categories as per the ISCO would allow for a better comparison of the occupations worldwide and help develop targeted vocational training programmes for them.

The corresponding ISCO-2008 codes for veterinary-related occupations are 2250 (for veterinarian), 3240 (for veterinary technicians and assistants), and 5164 (for pet groomers and animal care workers) (Fig. 1).

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) mapped human health workers to the ISCO. The WHO classification uses a hierarchical structure of occupational titles and ISCO codes, reflecting subgroups of the health workforce according to different skill levels and specialisations. The classification consists of health professionals, health associate professionals, personal care workers in health services, health management, and support personnel, and other health service providers not elsewhere classified [11].

Learning opportunities

Building on its work to date on veterinarian and VPP competencies and curricula, in 2021 the OIE will initiate a mechanism to build workforce assessment and development into the Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS) Pathway. This will respond to gaps and opportunities for countries to identify and address current and future workforce needs in the veterinary services, both public and private, and address service gaps such as are common in rural areas or in particular specialisations.

Being informed by trends and expertise in other sectors, including the standardisation frameworks discussed above, may help stakeholders in the veterinary field to tackle the long-term challenges that the veterinary sector faces in attracting and keeping young talent, building gender equity, and ensuring that professional development opportunities adapt to new technologies and evolving skills needs. In parallel, the OIE’s remit continues to involve helping to guide Members towards understanding and adopting the standards of the OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code and Aquatic Animal Health Code, in particular through guidance provided by the PVS Pathway services, such as PVS Evaluation missions, among others.

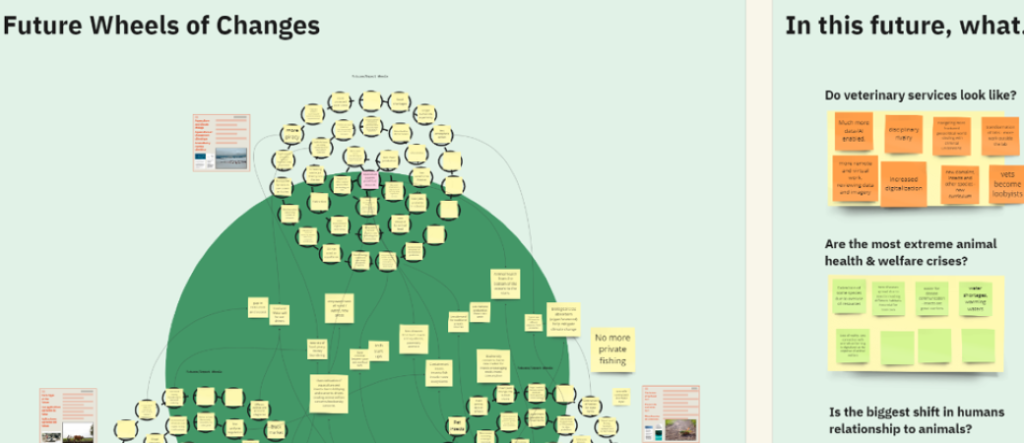

As the workforce development initiative progresses, it may be useful for the OIE to engage with other global initiatives related to workforce and educational planning and standardisation. The 20th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (10–19 October 2018) [12] endorsed a full revision of ISCO, to enable implementation in time for the 2030 global round of censuses coinciding with the end of the Sustainable Development Goals implementation period. The objective of the revision is also to widen the scope and international relevance of ISCO. Particular topics of note for discussion between the ILO and the OIE might include a) aligning occupational standards for the veterinary professions with the Terrestrial Code; b) including the roles of veterinarian, veterinary paraprofessional as well as community-based animal health worker; and c) further representing the needs of veterinary medicine aimed at the public good. The OIE welcomes stakeholder engagement from a range of actors as it embarks on its workforce development initiative.

References

- The European Qualifications Framework (EQF) | Europass. Available at: https://europa.eu/europass/en/european-qualifications-framework-eqf (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (nd). – ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework. Available at: https://asean.org/asean-economic-community/sectoral-bodies-under-the-purview-of-aem/services/asean-qualifications-reference-framework/ (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). Available at: https://www.saqa.org.za/ (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Lantra. Available at: https://www.lantra.co.uk/ (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Rural Skills Australia. Rural Skills Online Prime. Available at: https://www.ruralskillsonline.com/ (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Agriculture Skill Council of India (ASCI). Available at: https://asci-india.com/ (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF) (2012). – SCQF Level Descriptors. SCQF, Glasgow, Scotland, 34 pp. Available at: https://www.sqa.org.uk/files_ccc/SCQF-LevelDescriptors.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- National Skills Development Agency (India) (nd). – NSQF level descriptors. NSDA, New Delhi, India, 2 pp. Available at: https://www.nsda.gov.in/assets/documents/nsqf/NSQF%20LEVEL%20DESCRIPTORS.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute of Statistics (2017). – International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Available at: http://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/international-standard-classification-education-isced (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Wikipedia (2020). – International Standard Classification of Education. Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=International_Standard_Classification_of_Education&oldid=994053740 (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2010). – Classifying health workers: mapping occupations to the International standard classification. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, 14 pp. Available at: https://www.who.int/hrh/statistics/Health_workers_classification.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- International Labour Office (ILO) (2018). – Review of the case for revision of ISCO-08. ICLS/20/2018/Room document 19. ILO, Geneva, Switzerland, 32 pp. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—stat/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_636056.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2020).

http://dx.doi.org/10.20506/bull.2021.NF.3162

◼ OIE News – January 2021