INFORMATION EN CONTINU Posté sur 2021-04-30 12:21:01

Reflections on the Foot-and-Mouth Disease Epidemic of 2001: an Irish Perspective

Mots-clés

The designations and denominations employed and the presentation of the material in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the OIE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries.

The views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s). The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the OIE in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

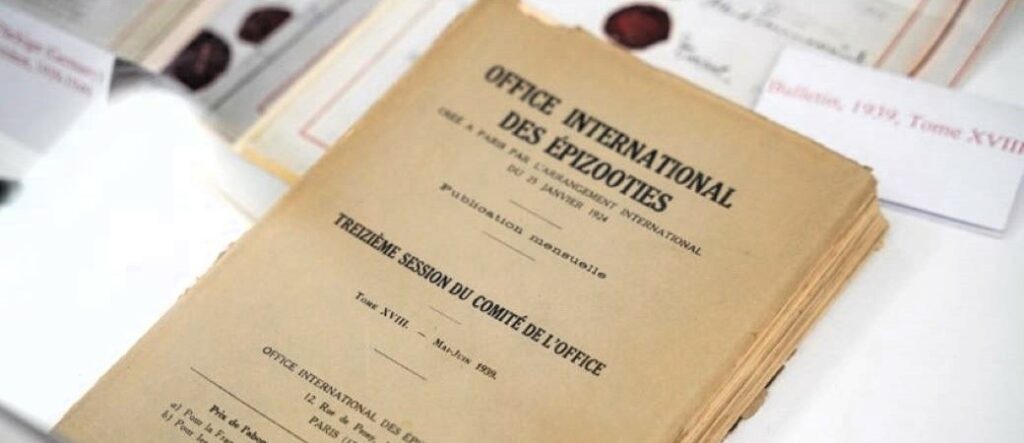

This year marks the 20-year anniversary of the foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) epidemic, which originated in the United Kingdom (UK) in February 2001, and subsequently spread to Ireland, the Netherlands and France.

Society has changed in many ways in that relatively short 20-year period since 2001. We have experienced the advent of social media, the rapid evolution of mobile phones with integrated cameras, the rise of ‘fake news’, the availability of drones that can be deployed over farms, the change in societal attitudes towards animals and disease control measures, and advances in modelling and laboratory diagnostic techniques. It is clear that the coverage of and response to an FMD epidemic on the same scale would be entirely different today. However, there are many lessons from 2001 that should not be forgotten and can be adapted to today’s contexts to better prepare us for future emergencies.

The OIE interviewed Dr Martin Blake, OIE Delegate for Ireland, who shared his personal memories and reflections from the time.

When People plan, God smiles.

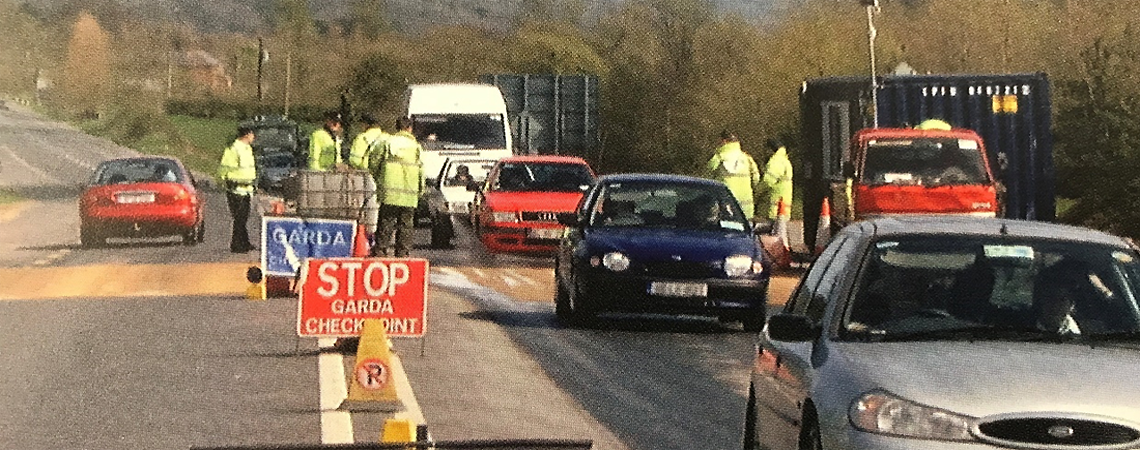

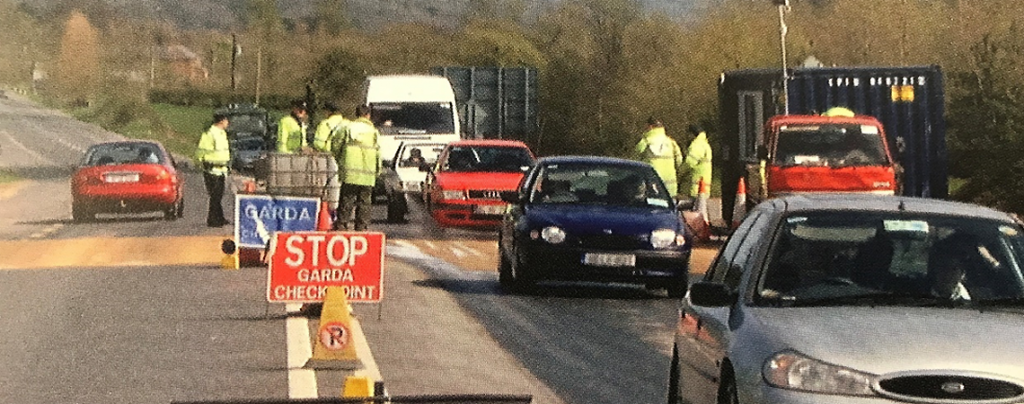

Dr Blake was working in a central policy role in January 2001 on zoonoses and animal welfare but, as the saying goes ‘When People plan, God smiles’, and FMD was soon on the horizon. Following confirmation of the disease in the UK on 19 February, an immediate response was implemented in Ireland due to its close relationship with Northern Ireland and Great Britain, and the risks posed to the Irish livestock industry. Within three to four days, the Gardaí (Irish police force) were supporting the Veterinary Services by enforcing disease control measures at borders and ports. The National Disease Coordination Centre (NDCC) was set up and Dr Blake described how he was assigned to it. It became clear for the NDCC and Ireland’s response to be successful that his role was to direct the operational response in relation to:

-

- ‘suspect’ investigations,

- managing the collation and sharing of information with senior management, politicians and the media,

- liaising with laboratories on testing capacities and capabilities, and

- liaising with the Investigations Team who were tracing of imports.

After awareness-raising campaign, it wasn’t long before suspected cases of FMD started to appear. Some staff had experience of control measures during the FMD outbreak in 1967 in the UK, and a senior emergency response colleague confided in Dr Blake ‘I don’t think anything can prepare you better than doing the job’. And by the end of February, the threat level had increased further when an outbreak was confirmed in Northern Ireland which led to animal movement restrictions and an end to routine veterinary work in Ireland. Horses are not susceptible to FMD but their movements had to be monitored given many were kept on livestock farms and they could potentially spread the virus. Dr Blake observed that ‘we never knew how much horses moved until we had to monitor it!’.

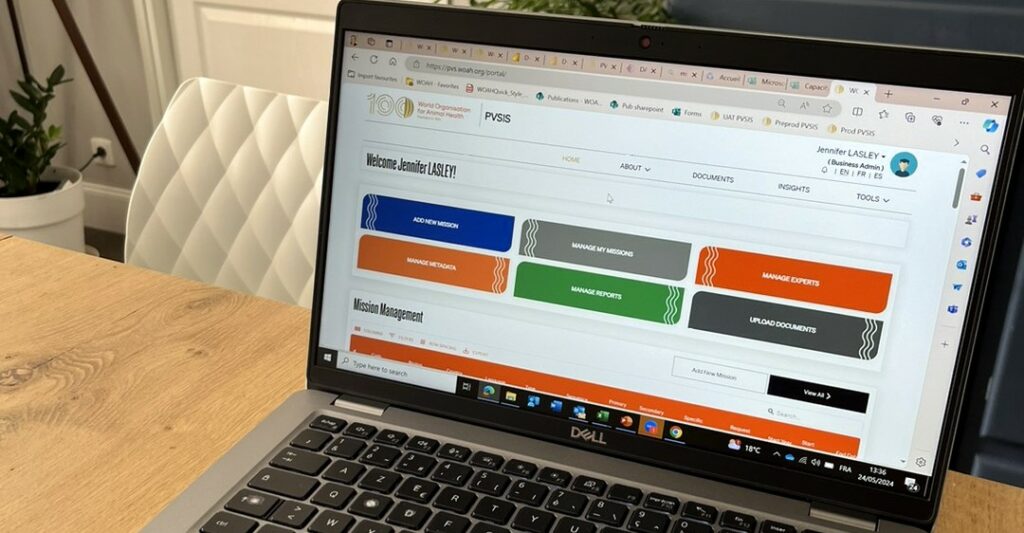

From 28 February to 1 March, control measures were ramped up and additional resources deployed to the border with Northern Ireland where a Local Disease Control Centre (LDCC) had been set up near Dundalk, Co. Louth, close to the border with Northern Ireland. The media were ravenous for information from the Government and a daily press conference was held which was fed by the information provided by the Veterinary Services. But decisions had to be made as to what could be shared and not shared at each stage, as any shared information had to stand up to tough scrutiny from the press. A key part of this decision-making process was the availability of information and ease of communication. At the time, the Department of Agriculture in Ireland was just transitioning into the use of e-mail, which was only in use in its main offices, in addition, not everyone had a mobile phone, so ‘truckloads’ had to be purchased, creating a crucial role for the logistics team in the response. These concerns simply wouldn’t factor into the response nowadays owing to the ready availability of such technology.

The immediate priority was making sure the farmer was told the results before it was announced publicly.

But things were about to switch gears when on 21 March there was a report of a suspected outbreak on a farm on the Cooley Peninsula in County Louth. Dr Blake vividly recalled the next day when the test results were shared with him, ‘I was on the backstairs in Agriculture House in Dublin after a meeting with the Chief Veterinary Officer and I got the call confirming FMD on the farm. The immediate priority was making sure the farmer was told the results before it was announced publicly’. The Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) later confirmed the outbreak publicly. Fortunately, prior to confirmation of the disease, the groundwork had already been laid for a whole-of-government response as the Taoiseach or the Minister for Agriculture had been chairing Cabinet meetings on FMD thus elevating its importance. This facilitated resource mobilisation when it was needed, including personnel from other departments and agencies such as law enforcement and the army.

A hotel close to the infected farm had been requisitioned to serve as an LDCC. IT equipment was sourced and transported to the location and staff were deployed from other parts of the country. Veterinary officers would arrive each morning and receive a list of farms on which to carry out surveillance inspections that day. Ireland took a precautionary approach and if disease was suspected, the animals were swiftly culled and samples taken to test for the disease.

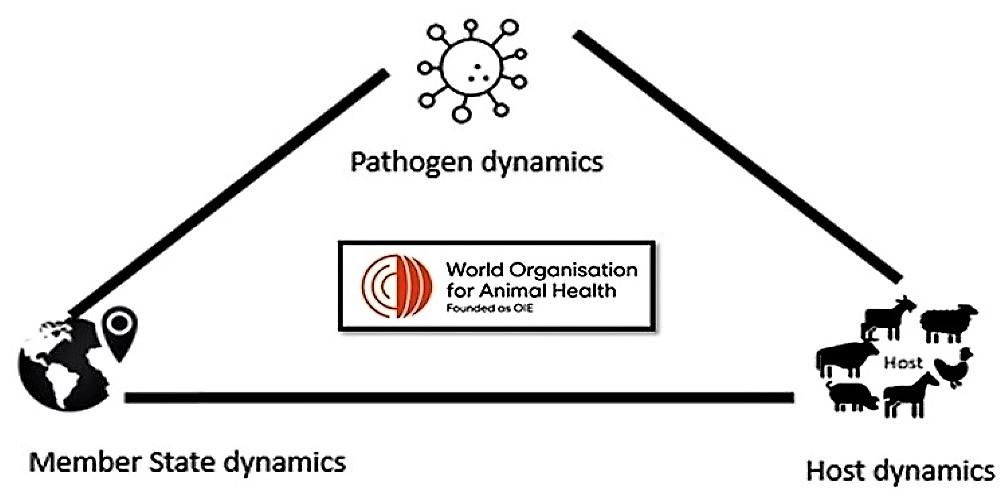

The Department was assisted in its response by a scientific advisory group set up by the CVO and chaired by the Dean of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of University College Dublin. It was purposely created as a multi-sectoral group and its members included experts from animal health, trade and business. This multi-sectoral approach helped take the pressure off veterinary staff as questions were sent to the group allowing a broad, transversal, whole-of-society response to queries that also influenced policy.

The situation began to settle around Easter (mid-April) and after three weeks of intensive work, staff were allowed some time off over the Easter weekend. Dr Blake remembered driving across the width of Ireland back home to Galway and just as he was pulling into the house, he received a call that Northern Ireland had confirmed its second outbreak close to the border. Easter festivities were cancelled, and staff were brought back in over the weekend to assist with surveillance visits and tracing. Police were called in to assist in the tracing of illegal import of suspect sheep. A decision was also taken to cull all the sheep in the peninsular area around the outbreak, as well as wild goats and deer which were on common grazing on the Cooley Mountains.

From April to September, surveillance continued, and the country tried to restore its OIE FMD-free without vaccination status which was confirmed on 19 September 2001. Dr Blake emphasised the importance of agriculture to Ireland and described the significant trade impacts that the outbreak had, and the importance of liaising with Ireland’s embassies and trading partners abroad to spread the news of this restored status. Significant time and resources were invested by the NDCC in the task of proving disease freedom.

Were we successful? Yes! Were we lucky? Yes…

In addition, as part of regaining FMD-free without vaccination status, extensive serological surveillance was undertaken primarily on sheep which show less obvious clinical signs of FMD than other species. A stratified sampling regime was undertaken with thousands of sheep sampled across the country in the summer period. This represented a major logistical challenge and involved Department staff and private practitioners, but the farming community cooperated fully and understood why it had to be done. ‘Were we successful? Yes! Were we lucky? Yes, the outbreak was in a peninsula, but we learned about the importance of resilient people and systems’ concluded Dr Blake.

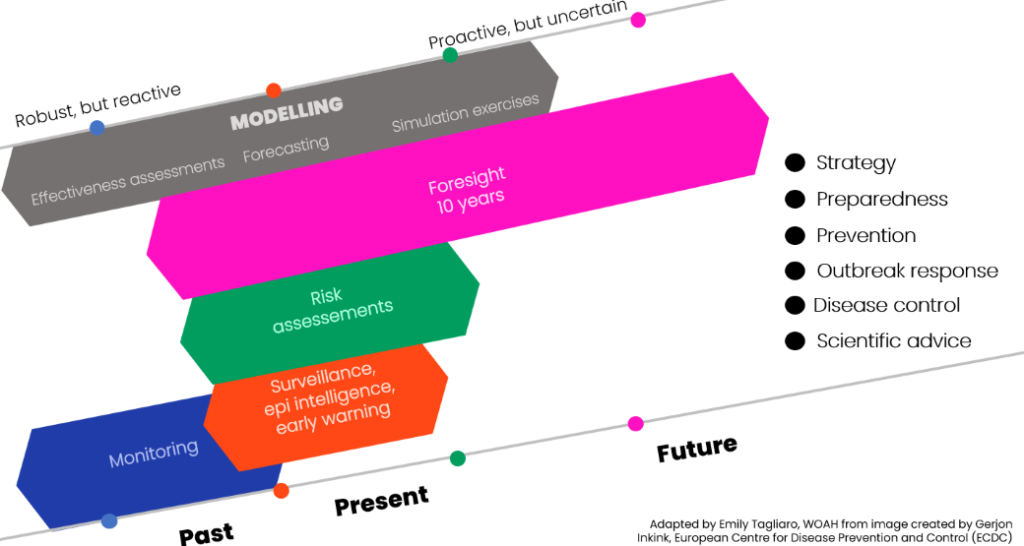

The FMD outbreak brought about changes in Ireland where new measures were put in place, including mandatory tagging of sheep, a new traceability system for livestock and the licensing of livestock dealers. Modelling has also advanced, and Ireland can now make greater use of this for future emergencies as has been done for the COVID-19 pandemic.

‘Ní neart go cur le chéile’ (There’s no strength without unity). When everyone pulls together it is amazing what you can do!

When asked to share his top lessons from FMD 2001, Dr Blake highlighted that:

-

- We need to contextualise events and recognise the broader impacts on society in areas other than agriculture and take a whole-of-government approach to emergencies to combine resources and as the Irish saying goes ‘Ní neart go cur le chéile’ (There’s no strength without unity).

- Consider the well-being of other people and the toll an emergency can take on them and ensure support is there if needed. We just have to look at COVID-19 and its impact on health care workers.

- Be open to new ways of doing things, for example emergency vaccination for FMD was not contemplated as a control measure at the time.

- Response ultimately depends on early diagnosis which includes the expertise of the clinician and capacity and capabilities of the laboratory which is sometimes forgotten when there is not an emergency.

When asked how we can better prepare the next generation of veterinarians and veterinary paraprofessionals for future emergencies, Dr Blake noted that ‘younger staff are tremendous and see things we do not see but they may lack direct practical experience of events such as this. They need to 1) participate in simulation exercises, 2) be aware of the importance of technical expertise, including crisis management communications and early diagnosis, and 3) engage in bespoke training and this includes opportunities like that provided by the European Commission for the Control of FMD (EuFMD)’.

Lastly, Dr Blake concluded that the outbreak taught him the importance of resilience and the ability to go with the flow and not internalise issues. ‘It is important to believe in yourself, listen to those around you and ensure decisions are still able to be taken in a timely manner during an emergency’.

We wish to thank Dr Martin Blake, the OIE Delegate for Ireland, for his contribution to the OIE News.

https://doi.org/10.20506/bull.2021.NF.3165

n OIE News – April 2021