INFORMATION EN CONTINU Posté sur 2021-08-24 10:38:28

Current state and future of small companion animal practice in Africa

Mots-clés

Authors: P. Bastiaensen1 & G. Varga2

(1) OIE (AFSCAN Board Member) Nairobi, Kenya; (2) ZOETIS (AFSCAN Board Chair), Brussels, Belgium

A selection of preliminary results of a continental survey in 2021

Developing private veterinary practices on a continent where most countries are low- to middle-income, with limited purchasing power (disposable income) and shifting attitudes to pet ownership is a challenge, especially outside of the very large and urbanised centres that host significant expatriate communities. In the run-up to the first African Small Companion Animal Congress, organised in June and July by the African Small Companion Animal Network (AFSCAN) a World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Foundation initiative, supported by the OIE, a continent-wide online survey was conducted on the current state and future of small companion animal practice in Africa. This article provides some preliminary insights into how private veterinarians running small companion animal surgeries in Africa are faring.

In the run-up to the first African Small Companion Animal Congress, organised by the African Small Companion Animal Network (AFSCAN) a World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Foundation initiative, supported by the OIE, a continent-wide online survey was conducted on the current state and future of small companion animal practice in Africa. The Congress took place from 29 June – 3 July 2021 and the survey was conducted from 2–21 June 2021 in three languages: English, French and Portuguese. The survey targeted a broad spectrum of professionals, from private practitioners to deans, lecturers, researchers and students at veterinary education establishments, representatives of veterinary statutory bodies and professional associations, as well as non-governmental/civil society organisations. The organisers of the survey received 120 submissions, most of them from the Republic of South Africa, Kenya and Ethiopia, but overall from 30 African countries.

While the survey and response rate could have been improved, it does provide novel insight into a sector that has long been overlooked in the African veterinary landscape. The following results are based on the responses from private veterinary practitioners only, totalling 55 submissions. Also, the following section focuses on open questions regarding the challenges of running a private veterinary practice, clinic or surgery in Africa, rather than on quantitative information e.g. the level of equipment and services available in their facilities.

Based on the feedback provided by private veterinarians, challenges can be grouped into four broad categories, in order of decreasing frequency:

- Getting the money in – Without a doubt the biggest challenges relate to finances and the economic model of small animal practice in developing and in-transition economies, characterised by low purchasing power of the public in general and pet owners in particular. There is a clear disconnect between what clients expect and what they can pay for, leading to many efforts being directed to debt servicing and recovering overdue bills. Many veterinarians warn of decreasing revenues because of decreasing numbers of clients or more pro-bono work done, less debt recovery and the increasing overhead costs of running a surgery.

- Time management – Many veterinarians struggle with work-life balance, long working hours, difficulties attracting suitable veterinarians, veterinary nurses and locums, and personal work stress and stress of staff members, often generated by unruly, irrational or misbehaving (human) clients. Another challenge is the time spent on non-clinical tasks such as human resources, administration, billing, and stock keeping, where some colleagues recognise that they neglect these tasks, whereas others lament that they put in too many hours, to the detriment of the clinical work.

- Cost, reliability and proximity of services – In small ‘niche’ markets such as the emerging small animal practice, it is still very challenging to secure (confirmatory) laboratory diagnostics and waiting times may be excessive, specific (novel) drugs may not be registered for use in the country and are either procured at excessive cost or imported directly from abroad; the same applies to the latest technologies and equipment, for which local suppliers (and maintenance and calibration services) are missing.

- Unfair competition – Unfair competition is mentioned in relation to some non-governmental organisations, such as animal welfare charities, who provide certain services free of charge (spaying, castration). In addition, concerns in French-speaking countries (except for Madagascar, mostly situated in West and Central Africa) are the scourge of fake or ‘barefoot’ veterinarians, and the related problems of the circulation of counterfeit drugs, illicit sales of drugs by unqualified vendors and the tradition of self-medicating before seeking professional help.

When asked how they see the future of their profession in the African context, most private veterinary practitioners seem optimistic, with 91% of them agreeing that ‘the future is bright’. Indeed, two out of three respondents (66%) reported an increase in pets as part of total animal numbers and revenue since the practice/surgery was established, while 14% saw no difference and 19% lamented a reduction in numbers and revenue.

One of the panel discussions during the Congress being the mental health of veterinarians in Africa, a final question was included referring to the emerging suicide rates of veterinary practitioners in many parts of the world (addressed by the Not One More Vet campaign, among others):

‘Irregular hours, high work pressure, client expectations and loneliness are major contributors to mental health disorders among private veterinary practitioners and higher-than-average suicide rates. From my perspective, I can relate to this.’

Overall, 8 out of 10 private veterinary practitioners stated that they could relate to this statement (or that on average, private veterinary practitioners relate ‘somewhat’ to this statement).

Even with all of its shortcomings and a weak response rate, this survey provides – probably for the first time – a birds-eye view of the sector, with interesting insights (and diversity between regions) into an emerging private veterinary corpus, currently primarily in urban areas, but in the near future undoubtedly also in provinces and districts of Africa.

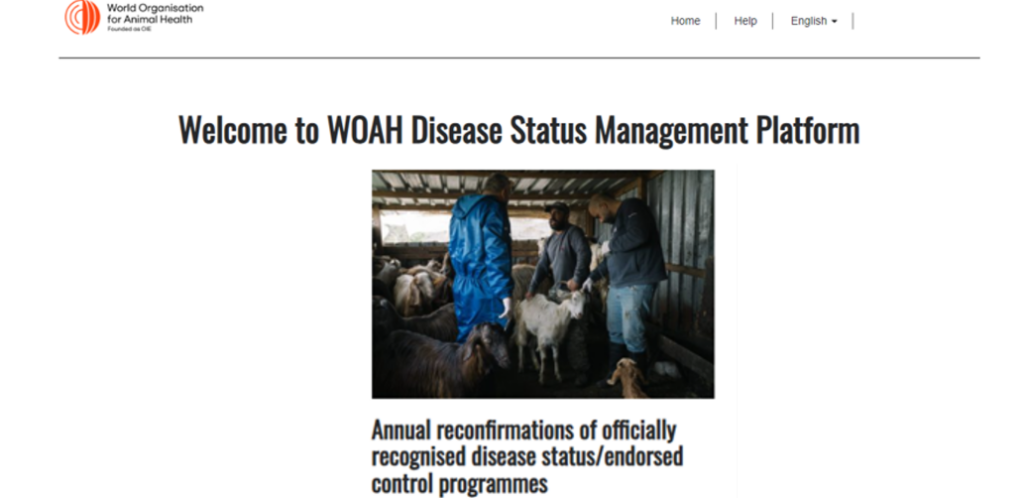

Ethiopian veterinarian Netsanet Sitotaw provides rabies vaccinations in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

Photo credit: ILRI/Mekdes Zenebe