INFORMACIÓN CONTINUA Publicado en 2020-12-29 15:32:01

Overcoming the impact of COVID-19 on animal welfare:

COVID-19 Thematic Platform on Animal Welfare

Palabras clave

Authors

N. De Briyne (1)*, P. Dalla Villa (2)*, D. Ellis (3), G. Golab (4), K. Gruszynski (5), A. Hammond-Seaman (6), S. Moody (1), Z. Noga (7), E. Pawloski (5), M. Ramos (8), H. Simmons (3), J. Tickel (3) & G. Vroegindewey (5)

(1) Federation of Veterinarians of Europe (FVE), Avenue Tervueren 12, 1040 Brussels, Belgium

(2) Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e del Molise ‘G. Caporale’, via Campo Boario, 64100 Teramo, Italy

(3) Institute for Infectious Animal Diseases (IIAD), Texas A&M University System, United States

(4) American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), 1931 North Meacham Road, Suite 100, Schaumburg, Illinois, United States

(5) Lincoln Memorial University College of Veterinary Medicine (LMU CVM), Tennessee, United States

(6) RSPCA, Wilberforce Way, Southwater, Horsham, West Sussex, RH13 9RS, United Kingdom

(7) World Veterinary Association (WVA), Avenue Tervueren 12, 1040 Brussels, Belgium

(8) National Animal Health and Agrifood Quality Service (SENASA), Av. Paseo Colón 367, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

* Corresponding authors: P. Dalla Villa and N. De Briyne

The designations and denominations employed and the presentation of the material in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the OIE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries.

The views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s). The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the OIE in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

Summary

Introduction

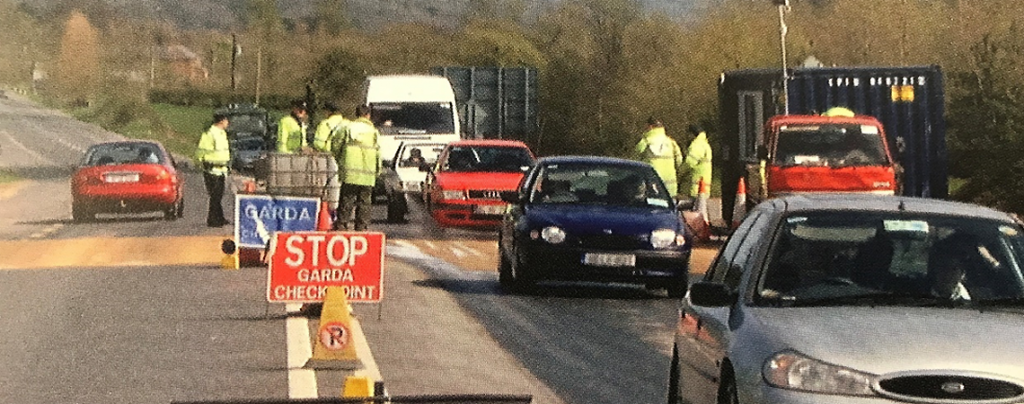

Starting from the first half of 2020, COVID-19 – caused by infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus – spread through almost all countries in the world. Many countries introduced country-wide or regional lock-downs to reduce the spread of infection. While the lockdown measures varied slightly per country/region, almost all countries closed schools and non-essential shops, bars and restaurants. Only essential businesses and key workers were allowed to continue working and travelling whilst social activity outside the home ceased. At the time of writing, many countries are still fighting to contain SARS-CoV-2 virus, whilst trying to address the resulting economic challenge that has sent many countries spiralling into the worst economic crisis since World War Two.

The psychological toll on people due to the anxiety caused by the novel virus, and also by the harsh isolation and social distancing measures imposed to prevent the spread of the virus, will only be truly known years from now. However, mental health professionals and institutions are already ringing alarm bells [1].

The crisis caused by this pandemic does not only affect people. Animals are indirect victims of the pandemic too. COVID-19 has had, and will continue to have for some time into the future, an impact on the health and welfare of almost all animals, including companion animals, livestock, laboratory animals and wildlife.

The COVID-19 Thematic Platform on Animal Welfare was created in April 2020 to oversee and try to reduce the impact of this pandemic on animals.

Setting and composition of the network

In early April 2020, the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e del Molise ‘Giuseppe Caporale’ (IZSAM) brought together several global institutions and experts who were dealing with the animal welfare impacts of the pandemic to form the COVID-19 Thematic Platform on Animal Welfare.

IZSAM provides the Secretariat for the three OIE Collaborating Centres with a veterinary emergency focus. These centres are known as the Emergency Veterinary Network (EmVetNet). The other two EmVetNet centres are the Institute for Infectious Animal Diseases at Texas A&M University, United States of America (USA), and Centro Nacional de Sanidad Agropecuaria (CENSA) in Mayabeque, Cuba. The aim of EmVetNet is to provide OIE Members with advice and technical assistance during events that have catastrophic or widespread impact on animal health. EmVetNet also promotes the sharing of knowledge on best practices (including models and case studies, e.g. model legislation, contingency/emergency plans, communication) and provides training, capacity building, exercises and evaluation across the emergency management cycle for all hazards at the international level. COVID-19 is, without doubt, a hazard that urgently needed intervention. This led to the setting up of the COVID-19 Thematic Platform on Animal Welfare, within the framework of the EmVetNet 2020–2024 action plan.

With the current crisis, it is crucial that, amongst other activities linked to animal disease prevention and management and food and feed safety and security, Veterinary Services can ensure that critical situations can be adequately managed when animal welfare is at risk.

Starting in April with just a few members, the COVID-19 Thematic Platform on Animal Welfare quickly grew to a global network of experts, stakeholders and institutions from different sectors. Between early April and September, eight meetings of the network were held.

Crucial to the work of the network was the extensive support given by Lincoln Memorial University (LMU) College of Veterinary Medicine, which dedicated 18 veterinary students, 2 undergraduate students, 7 veterinary faculty and 3 staff to support the network by collecting, fact checking, collating and analysing all data sources on the welfare impact of COVID-19.

Members of the network

Aims and methodology

The aim of setting up this network was to bring together worldwide institutions and experts, all working together to assess and describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on animal welfare in order to exchange information, policies and good practice to prevent or alleviate welfare concerns, while also taking into account the needs for disease prevention, food security and food safety. Specifically, the network serves a supporting role for Veterinary Services within OIE Members to cope with the impacts of COVID-19 on animal welfare.

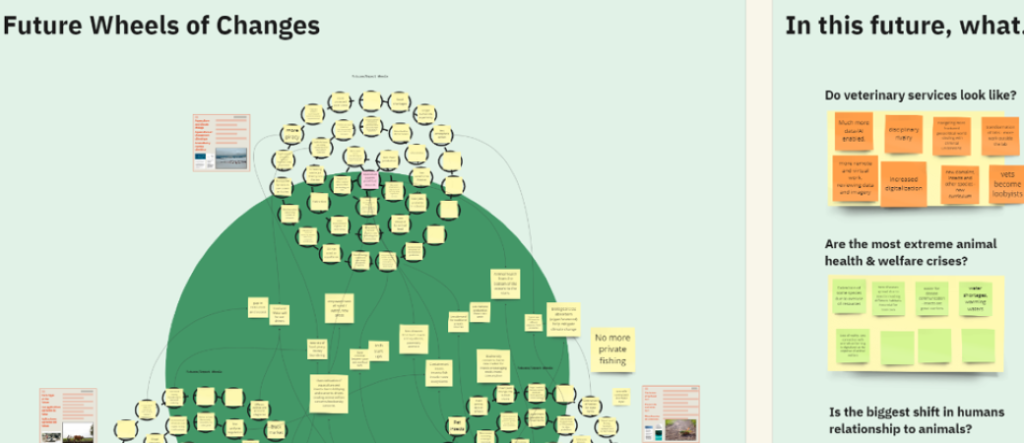

The network started with members mapping the animal welfare consequences of COVID-19 in their country/region or discipline, such as the abandonment of companion animals and closing of slaughterhouses.

Following the initial phase, an inclusive and automated method was developed to retrieve information on the animal welfare impacts of COVID-19 from all over the world. This was done by programming an online survey using the Qualtrics platform. This platform allows information to be collected and helps to analyse data. The online survey was created so that it could be easily completed on both computers and mobile devices.

The survey asked respondents for the following information:

- links for information sources (e.g. publications, news articles, personal communication and media) on the animal welfare impacts of COVID-19

- details, including the URL, of the information sources

- the theme(s) of the information (e.g. legislative, educational, logistics, communication, species covered)

- the OIE reference region to which the material referred

- the time frame of the impact (short – less than two months; medium – two to six months; long term – longer than six months)

- whether there was a concurrent or cascading issue (e.g. another disease or weather event)

- a short description/narrative.

The survey was first piloted among the network members, and afterwards published online.

In addition to the online survey through the Qualtrics platform, the students from LMU searched a variety of sources, ranging from peer-reviewed articles to grey literature.

The LMU students collected all information received through the mapping done by the network, the Qualtrics platform and their own research, and brought it together, through narrative, by topic and by species, e.g. the abandonment of horses.

Results

At the end of the summer project on 6 August, input had been received on 118 countries representing all OIE regions. The majority of inputs came through research by the LMU students with over 1,200 entries recorded.

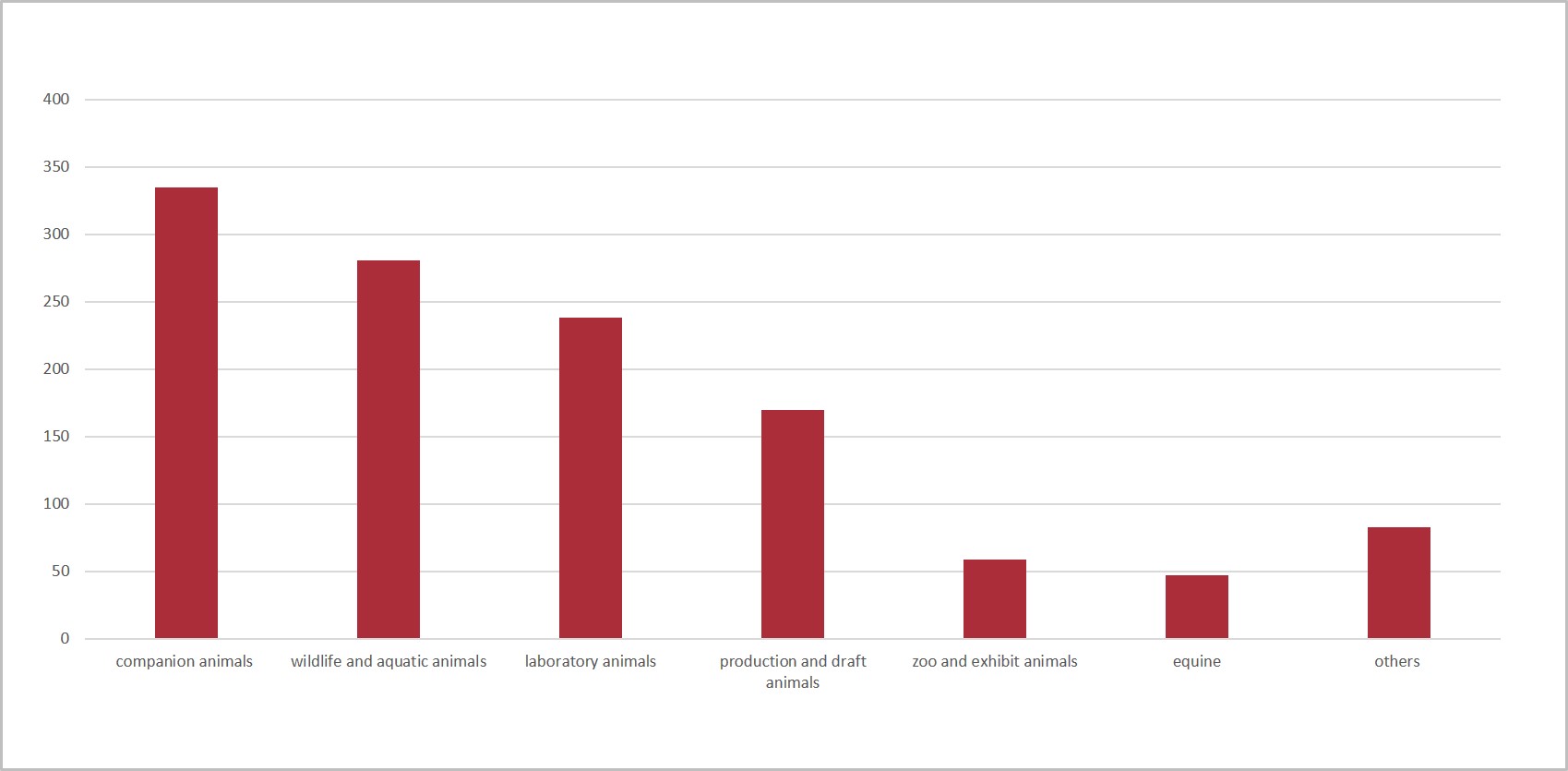

Most entries dealt with the impact on companion animals (335 entries); followed by the impact on wildlife and aquatic animals (281); laboratory animals (238); production and draft animals (170); zoo and exhibit animals (59); equine (47); and others (83). The group ‘others’ was used for entries providing material that was not specific to particular species (e.g. policy, economics).

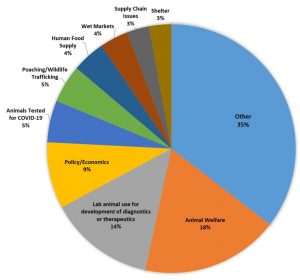

The major issues identified were: animal welfare (17.9%, n = 309); laboratory animal use for the development of diagnostics/therapeutics (13.8%, n = 238); policy/economics (8.6%, n = 149); animals tested for COVID-19 (5.5%, n = 94); and poaching/wildlife trafficking (4.9%, n = 85).

Almost 25.8% of materials not only described the challenges resulting from COVID-19 but also proposed solutions. Around 34.8% of materials referenced humans or disease in humans.

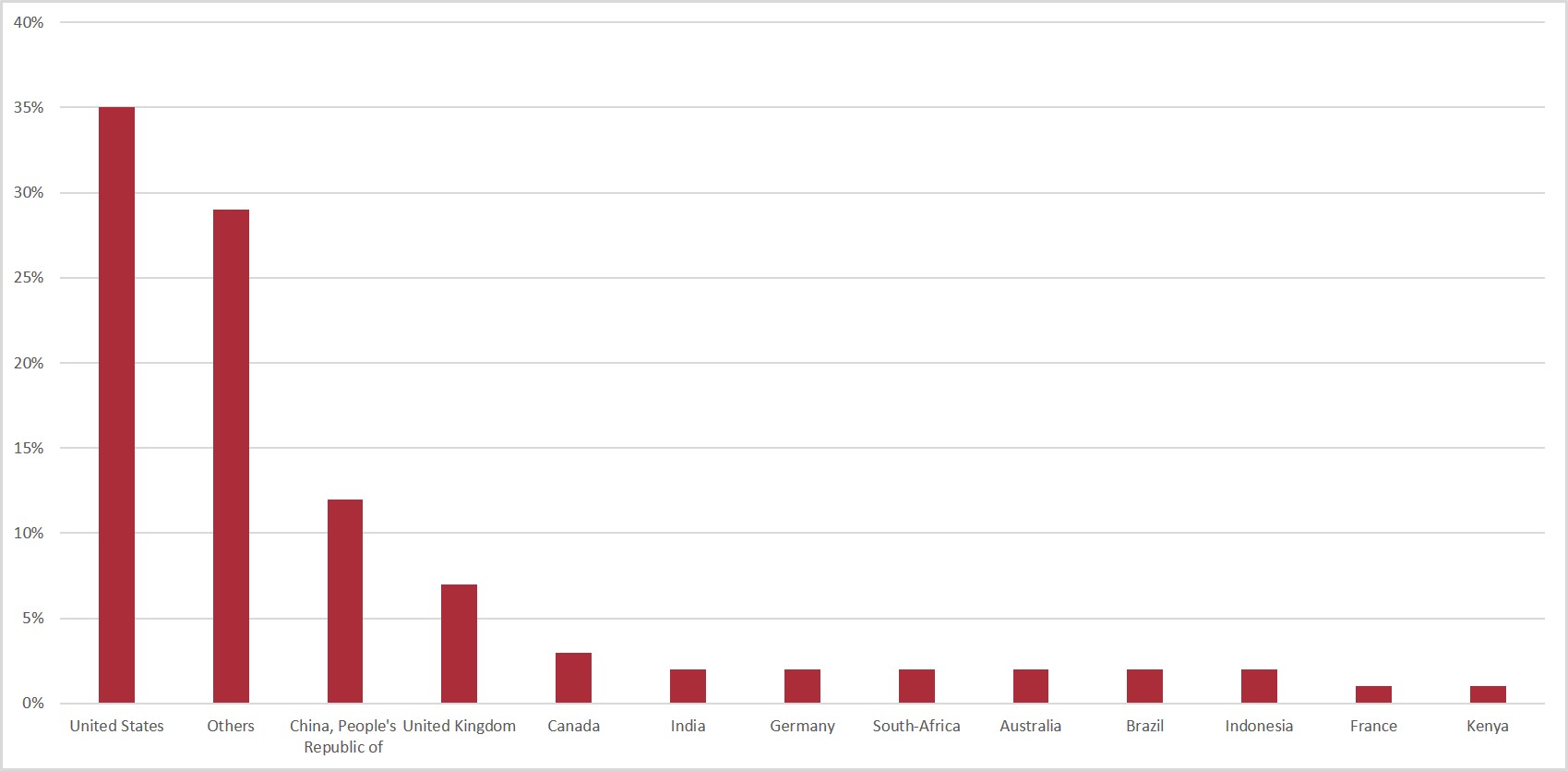

Figure 2 represents all countries (n = 13) that had 20 or more inputs in the database. The remaining 105 OIE Members and non-OIE Members made up 29% of all inputs.

Figure 3 represents what the students considered to be the focus of the material. Only issues (n = 9) with 50 or more entries in the database were included. The remaining issues were grouped as ‘other’.

The students developed 64 COVID-19-focused narratives which were reviewed by the faculty for use by EmVetNet members. The narratives were grouped into thematic areas: equines (7); production and working animals (8); companion and shelter animals (13); laboratory animals (6); zoos and wildlife (14); public health (8); and policy and legislation (8). Examples of narratives from each group included:

- equines: abandoned horses, equine COVID-19 testing, equine business impacts

- production/working animals: depopulation due to slowdown of slaughtering, COVID-19 infection in mink, COVID-19 detector dogs, feed shortages, sheep shearer shortages

- companion and shelter animals: shelter influx of relinquished animals, China banning dog meat, shelter economics, the shortage of adoptable pets

- laboratory animals: use of non-human primates for testing, shortage of laboratory mice for research, small animal COVID-19 models

- zoos and wildlife: wildlife poaching, economic impacts on zoos, impacts of the decrease in trophy hunting, deforestation

- public health: the well-being of veterinary personnel, the impact of COVID-19 medical care on other diseases, veterinary laboratory support for sampling humans

- policy: wet-market and live-market slaughter bans, personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages and PPE litter.

All narratives were circulated among the network’s members for review and discussion.

The network is currently working on publishing its main findings and solutions to the wider public. This will be done through the EmVetNet website and possibly via an interactive visual database.

Discussion

Through their research, the authors found that COVID-19 has had or will have further impacts on the health and welfare of almost all animals, including companion animals, livestock, laboratory animals and wildlife, and that the impacts are global.

The World Economic Outlook (WEO) report of June 2020 for the International Monetary Fund projects global growth at −4.9% in 2020, 1.9 percentage points below the April 2020 WEO forecast [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a more negative impact on activity in the first half of 2020 than anticipated, and the recovery is projected to be more gradual than previously forecast. The adverse impact on low-income households is particularly acute, imperilling the significant progress made in reducing extreme poverty in the world since the 1990s.

The World Bank in its August brief warned about a potential rise in food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic [3]. Accordingly, many countries and organisations are mounting special efforts to keep agriculture running safely as an essential business, ensuring that markets are well supplied within affordable and nutritious food, and that consumers are still able to access and purchase food despite movement restrictions and income losses.

Animals play an important role in our society. Not only do they constitute a significant part of our food chain, but they are also our loving companions, and often our co-workers. The COVID-19 pandemic threatens the welfare of animals of all kinds.

Livestock animals have experienced the effect that COVID-19 has had on the food production sector. The impact was two-pronged in lockdown: the meat trade was disrupted, while simultaneously people’s consumption habits changed [4]. With restaurants, schools and canteens closed, people sought more basic ingredients (flour and eggs) and preferred more cost-effective types of meat over expensive steak or fish. Locally sourced food and online shopping have become much more popular [5]. While the market can absorb some changes by using warehouse storage, this is not possible for any length of time or for every meat product. As a result, some farmers have not been able to sell their animals. Abattoirs and meat-packing plants became hot spots for COVID-19 [6]. This has been observed in many European countries and those on the American continent, as well as globally. Slaughter plants, some of which are vast operations, have had to close down at short notice. This has led to welfare problems due to overcrowding on farms. Animals have been re-routed to other abattoirs, had their diets changed to slow their growth or, in the worst-case scenario, have been culled [7].

Companion animals have also suffered the effects of COVID-19 [8]. In some countries people have abandoned their animals due to fear of the virus [9], even though there is currently no evidence that pets can spread COVID to humans [10]. Others have been relinquished because their owners had to move out of an infected area or be hospitalised. In other countries, the number of adoptions has increased, but it is not clear whether these new owners will be able to look after their new pet once they go back to work. It is strongly recommended that owners prepare their pets for when they have to return to work in order to prevent separation anxiety. At the height of the pandemic many countries stipulated that only urgent or emergency procedures absolutely necessary for the veterinary healthcare of companion animals could take place. Delays in routine care (e.g. vaccination, parasite prevention) has led to some serious health and welfare problems, as well as an overflow of work after the restrictions were lifted which, in turn, has created additional delays in the delivery of these services.

Finally, but maybe most worrisome, is the potential impact that the economic recession will have on the ability of owners to pay for healthcare and feed for their animals. This is of particular concern for animals that are more expensive to keep, such as horses, which have steep maintenance costs. This is even more pertinent in the light of the 2008/2009 economic recession which resulted in a large increase in horse euthanasia and abandonment [11].

In the field of laboratory animal medicine, many research institutions had to temporarily shut down their facilities and find ways to continue to care for the animals on site. At the same time, the direction of biomedical research shifted to support the response to COVID-19 and there was an enormous increase in demand for transgenic mice and ferrets for use in research directed towards vaccines and treatments [12].

As a last point of interest, zoos have had a particularly hard time [13]. Most zoos rely on visitors for income, while feeding and maintenance costs are very high. Conservation work is suffering. Some zoos did not survive, and solutions had to be found for their animals. Others are still struggling.

These are just a few examples of how animals are collateral victims of COVID-19, but many more exist. The good news is that veterinarians can mitigate these effects and, as a profession, we have the potential to be at the forefront of doing so.

Challenges such as COVID-19 seldom present themselves in isolation. In several countries, the effect of COVID-19 was amplified through other diseases or disasters, such as the explosion in Beirut, African swine fever in Europe and wildfires in the western USA.

The veterinary profession has the potential to prevent or alleviate the impact on animal welfare caused by COVID-19: this thematic network provides the tools and resources to do so

Veterinary Services, as defined by the OIE [14], include all official and private veterinarians, who provide important animal and public health disease surveillance to prevent infectious outbreaks, including zoonotic diseases. They ensure food security so that people have safe food to eat by ensuring only healthy animals and their products can enter the food chain. Veterinarians provide ongoing medical care and oversight as well as surgical and emergency services to ill and injured animals. Veterinary Services also include the national and regional veterinary regulatory and inspection services that oversee the integrity of public health. They supervise veterinary services provided in animal hospitals, mobile clinics, ambulatory services, zoos, etc. In addition, they oversee the care of laboratory animals, which are critical to research medicines and vaccines, including vaccine research against viruses such as COVID-19.

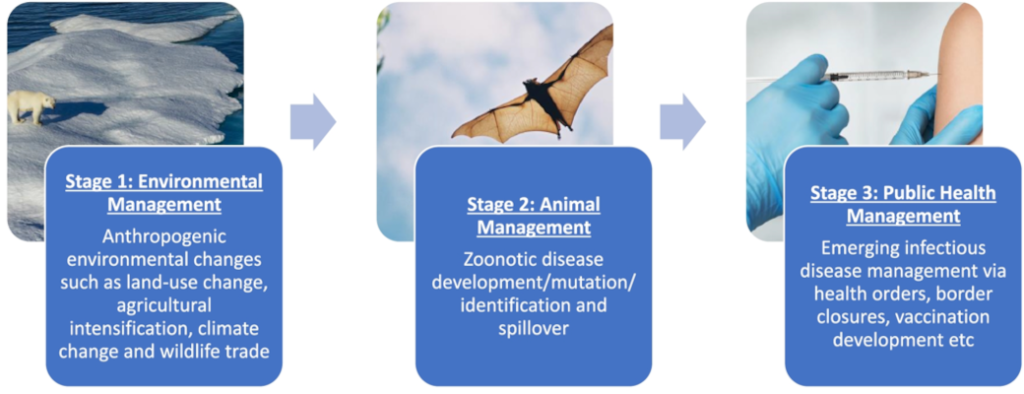

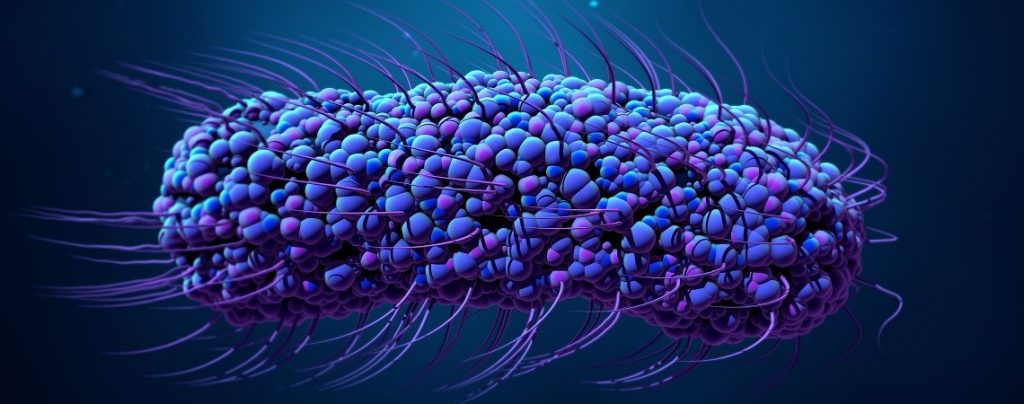

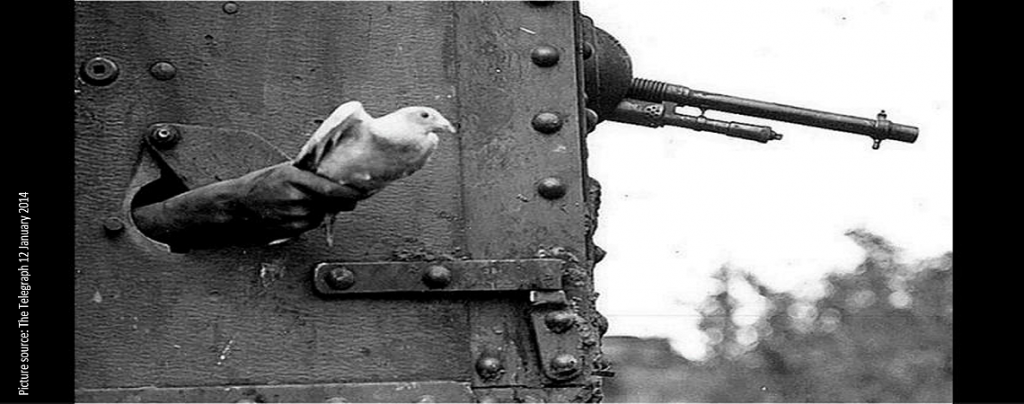

COVID-19 is a zoonotic infection. It is most likely the result of a leap from bats that act as a reservoir to an intermediate host (the best candidate is the pangolin [15]), and from there to humans (spill-over), in a similar transmission mechanism to those of the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses [16]. Although the disease has a largely human impact, collaborative efforts have recognised and acknowledged the connection between animal and human health, an interrelationship inherent in the One Health concept. Veterinary laboratories supported COVID-19 testing for humans, veterinarians volunteered in hospitals and veterinary practices provided equipment such as ventilators. In a novel example of humans and animals working side by side, sniffer dogs are trained to detect COVID-19 in patients [17]. Dogs are now being used to sniff passengers at Helsinki–Vantaa airport in Finland [18]. Solutions for dealing with the consequences of both the virus and our response to it have again brought to light the importance of One Health. Recognising and documenting these One Health impacts during the pandemic has facilitated robust discussions and a more holistic approach among those participating in the response.

The whole veterinary profession (including veterinary officials, private practitioners, and those working in research, academia and industry), by working together and sharing experiences, solutions and best practices, can alleviate the impact of this pandemic on animals. Additionally, and even more importantly, critical intervention points can be identified, and lessons learned which can improve our response to future emergencies or pandemics.

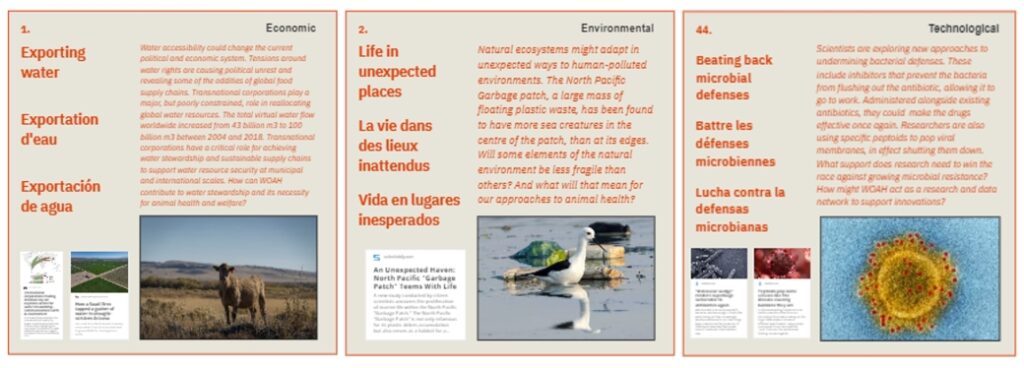

It is expected that this pandemic will not be the last. The zoonotic impact of COVID-19 has been relatively minor; this could well be different for future viruses. Any pandemic will have negative impacts on people, animals and our planet, but we can prepare for them and influence their effect. Challenging times provide an ideal opportunity to question accepted norms and practices, as they bring to light the weaknesses in our existing approach to animal care and management. Rapid answers are needed, and the solution may well be found outside the usual scope.

Conclusion

EmVetNet has demonstrated the value of the rapid development and deployment of technology. There would be great worth in strengthening and expanding this network. EmVetNet has shown that there is a need for single source information on animals, and on animal welfare during disasters. Working in partnership with educational institutes has also increased student interest in non-clinical careers including public health, One Health, public policy, and global health. Truly, the work of the network has shown the value of collaboration and highlighted the need for reflection on what can be learned during a disaster and when reporting on its aftermath.

https://doi.org/10.20506/bull.2020.NF.3137

References

- World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe (2020). – Mental health and COVID-19 [accessed on 24 September 2020]. www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/technical-guidance/mental-health-and-covid-19.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2020). – World Economic Outlook Update, June 2020: a crisis like no other, an uncertain recovery [accessed on 24 September 2020]. www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/06/24/WEOUpdateJune2020.

- The World Bank (2020). – Food security and COVID-19 [accessed on 24 September 2020]. www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-and-covid-19.

- Marchant-Forde J.N. & Boyle L.A. (2020). – COVID-19 effects on livestock production: a One Welfare issue. Front. Vet. Sci., 7, 734. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.585787.

- Felix I., Martin A., Mehta V. & Mueller C. (2020). – US food supply chain: Disruptions and implications from COVID-19 [accessed on 25 September 2020]. www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/us-food-supply-chain-disruptions-and-implications-from-covid-19#.

- Politico (2020). – Germany reckons with second wave risk [accessed on 24 September 2020]. www.politico.eu/article/germany-coronavirus-second-wave-risk-gutersloh/.

- Polansek T. & Huffstutter P.J. (2020). – Piglets aborted, chickens gassed as pandemic slams meat sector. Reuters. 28 April 2020 [accessed on 25 September 2020]. https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-livestock-insight-idUKKCN2292YS.

- Parry N.M.A. (2020). – COVID-19 and pets: when pandemic meets panic. Forensic Sci. Int. Reports, 2, 100090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100090.

- Kim A. (2020). – Cats and dogs abandoned at the start of the coronavirus outbreak are now starving or being killed. CNN [accessed on 25 September 2020]. www.cnn.com/2020/03/15/asia/coronavirus-animals-pets-trnd/index.html.

- World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). – Questions and answers on COVID-19 [accessed on 25 September 2020]. www.oie.int/scientific-expertise/specific-information-and-recommendations/questions-and-answers-on-2019novel-coronavirus/.

- Owers R. (2017). – Unwanted horses – an NGO perspective [accessed on 25 September 2020]. https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/animals/docs/aw_platform_20171110_pres_05.pdf.

- Callaway E. (2020). – Labs rush to study coronavirus in transgenic animals — some are in short supply. Nature, 579 (7798), 183–183 [accessed on 25 September 2020]. www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00698-x.

- European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) (2020). – Reducing negative implications of COVID-19-related economic challenges for Members on population management in EAZA [accessed on 25 September 2020]. www.eaza.net/assets/Uploads/Mailing-uploads/2020/2020-05-EAZA-zoos-corona-consequences-animal-pops-final.pdf.

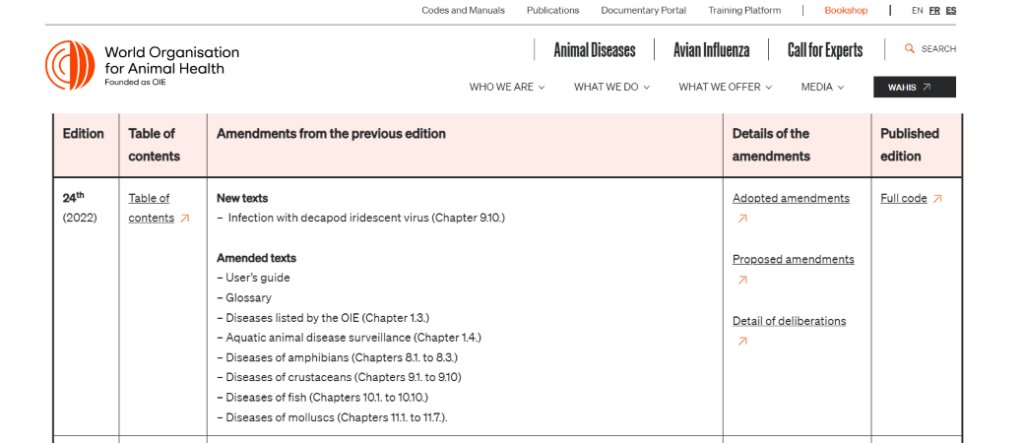

- World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) (2019). – Glossary. In Terrestrial Animal Health Code. www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahc/current/glossaire.pdf.

- Lee J., Hughes T., Lee M.H., Field H., Rovie-Ryan J.J., Sitam F.T., Sipangkui S., Nathan S.K.S.S., Ramirez D., Kumar S.V., Lasimbang H., Epstein J.H. & Daszak P. (2020). – No evidence of coronaviruses or other potentially zoonotic viruses in Sunda pangolins (Manis javanica) entering the wildlife trade via Malaysia. bioRxiv 2020.06.19.158717. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.19.158717.

- Ferri M. (2020). – Covid-19 and One Health. Covid-19 crisis management from a One Health perspective: can we do better? [accessed on 2 October 2020]. www.linkedin.com/pulse/covid-19-one-health-maurizio-ferri.

- Jendrny P., Schulz C., Twele F., Meller S., von Köckritz-Blickwede M., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Ebbers J., Pilchová V., Pink I., Welte T., Manns M.P., Fathi A., Ernst C., Addo M.M., Schalke E. & Volk H.A. (2020). – Scent dog identification of samples from COVID-19 patients – a pilot study. BMC Infect. Dis., 23 July 2020; 20 (1), 536. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05281-3.

- BBC News (2020). – Coronavirus: Helsinki airport trials sniffer dogs as Covid-19 detectors. BBC News, 24 September 2020 [accessed on 2 October 2020]. www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-54288067.

◼ October 2020