CONTINUOUS INFORMATION Posted on 2021-04-30 12:20:31

Reflections on the Foot-and-Mouth Disease Epidemic of 2001: a United Kingdom Perspective

Keywords

The designations and denominations employed and the presentation of the material in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the OIE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries.

The views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s). The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the OIE in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

The world is continuing to battle COVID-19, but 20 years ago, the United Kingdom (UK) faced another unprecedented event that would also require a whole-of-government response to tackle it.

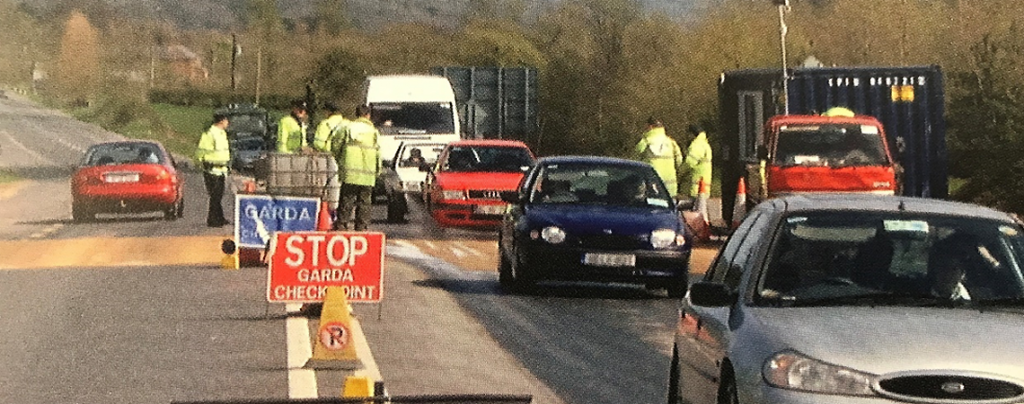

On 19 February 2001, the first case of foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) was detected and by 30 September 2001, over 2,000 premises were confirmed to be infected with more than 6 million animals culled (4 million for disease control purposes and 2 million for welfare reasons). The army and law enforcement were subsequently brought in to support the many veterinarians and field and support staff who were fighting the disease. The UK epidemic would also spread to neighbouring countries that included Ireland, the Netherlands and France. The preparedness and resilience of Veterinary Services in the UK was greatly challenged by this emergency and many lessons were learnt to improve contingency planning for future events.

The OIE asked Dr Christine Middlemiss, OIE Delegate for the UK, to share her personal experience from the time.

I volunteered to be part of the ‘veterinary army’

I was a vet working in Scotland, when FMD struck Britain in February 2001. Being from a farming background, and having later worked in mixed practice in Cumbria, I volunteered to be part of the ‘veterinary army’ in Cumbria to fight against this devastating disease.

The training provided on arrival in Carlisle was limited as we were urgently needed on farms to deal with the disease on the front line. There were some really hard times, but equally all of us, vets, technicians and administrators, felt a sense of purpose. We were working to get the disease under control and limit the impact on our farming communities. Communication was key, as it was vital to ensure that farmers and communities knew what we were doing and why.

As one of my primary duties, I carried out clinical examinations of cattle and sheep on farms, which was often followed, if disease was confirmed, by having to deliver the difficult news to farmers that their herds were infected and needed to be culled. It was devastating for them and their families who had often built up their herds over decades, but I vividly recall their support to our work, despite the horrible news we often had to deliver. It struck me that despite the terrible context, they were ready to work with us and were incredibly resilient and supportive.

The outbreak lasted 221 days and resulted in 6.45 million animals being culled

The first case of FMD was reported in Essex on 19 February 2001, followed by a second diagnosed case in Northumberland four days later. It quickly became clear that the disease had already spread across much of the country. Epidemiological evidence indicated that infected animal products had been imported from the Far East and had been used as animal feed on pig farms, creating the index case.

The outbreak lasted 221 days and resulted in 6.45 million animals being culled across the UK. It led to around £5 billion in costs to wider industry and society, highlighting the vast damage disease outbreaks could cause, both directly and indirectly. It had a lasting effect on individuals, including their mental health, as well as the broader agricultural sector and rural communities.

Farmers, vets, communities and government officials all worked closely together to eradicate the disease during a very challenging period, and we succeeded in achieving FMD-free status once again. The last case of FMD was confirmed in Cumbria on 30 September 2001, and the UK regained FMD-free status in January 2002.

[We] must continue to improve our disease contingency planning

The UK learnt critical lessons from the 2001 outbreak which has substantially improved our disease contingency planning. As a result of this we are now better prepared to tackle animal disease with farmers, vets and government scientists working in partnership to ensure the highest standards of disease prevention and control.

The changes we have made since 2001 to improve biosecurity on UK farms have been wide-ranging, one of the most prominent being the ban of feeding farm animals with swill and subsequent awareness campaign. We have also improved our livestock traceability, and we are now acting to further enhance our capabilities in this area. We are currently developing a new traceability system – the Livestock Information System (LIS) – alongside industry. This will drive innovation and improve our resilience and responsiveness to animal disease, as well as delivering a trade advantage. The UK is a global leader in animal science, but as the recent outbreak of avian influenza has shown, we can never be complacent and must continue to improve our disease contingency planning to protect animal health and further enhance our biosecurity.

The development of gene sequencing is a particularly impressive tool, and I am pleased that the UK, amongst others, is leading, with our real-life experience, on this work. It allows veterinary and public health scientists to track the movement of virus variants and determine the pattern of infection with greater confidence.

The lessons we learnt from the 2001 outbreak were tested with the re-emergence of FMD in 2007, which was halted before it spread beyond a handful of farms. Gene sequencing enabled us to see how the genetics of the virus changed with each infection. This allowed us to establish links between cases rather than relying solely on farm movement records and confirmed a very quick eradication of the disease in 2007. Our rapid response enabled us to limit the spread of the disease quickly and efficiently. This meant that only 81 premises were affected, a vast improvement compared to the 2001 outbreak where over 2,000 premises were infected.

Working collaboratively…is key

Working collaboratively with other government agencies on our prevention efforts is key. We continue to work closely with Public Health England, Department of Health and Social Care, the Food Standards Agency, Border Force and leading scientists to ensure that any potential risks to public health are fully explored and understood. I am particularly proud of our ongoing collaboration with Border Force to prevent future disease outbreaks. They manage our enforcement of illegal imports of products of animal origin at the border, and they hold regular discussions on animal health risks with the Chief Veterinary Officers. An example of our continued collaboration is Border Force’s assistance with our national awareness campaign for African swine fever which included the distribution of hard copy posters and digital screens across key areas of airports and ports, along with other Border Force messaging as part of a summer traveller campaign.

As I look back over the last 20 years, it is clear that it’s not just FMD control that has benefited from subsequent improvements in contingency planning – our capacity to deal with other diseases such as avian influenza has also been boosted from the lessons learnt. This has been particularly clear over the last few months while I’ve been busy managing the UK’s largest outbreak of avian influenza. We have taken swift action to bring in new housing measures across the UK to help protect poultry and captive birds. It has demonstrated that we can respond effectively even whilst working within the current constraints arising from COVID-19 control measures. The 2001 FMD outbreak was an incredibly difficult time for UK agriculture. However, we have continued to build on the lessons learnt from it and we are in a stronger position to respond effectively to disease outbreaks in the future.

Reference:

National Audit Office, NAO Report (2002), REPORT BY THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL HC 939 Session 2001-2002: 21 June 2002, The 2001 Outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease, https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2002/06/0102939.pdf

We wish to thank Dr Christine Middlemiss, the OIE Delegate for the UK, for her contribution to the OIE News.

https://doi.org/10.20506/bull.2021.NF.3166

n OIE News – April 2021